European honey buzzard

| European honey buzzard | |

|---|---|

| |

| Adult bird in Germany | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Accipitriformes |

| Family: | Accipitridae |

| Genus: | Pernis |

| Species: | P. apivorus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Pernis apivorus | |

| |

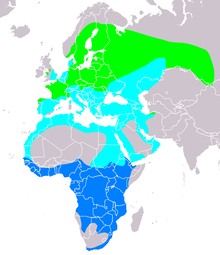

| Range of P. apivorus Breeding Non-breeding Passage

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Falco apivorus Linnaeus, 1758 | |

The European honey buzzard (Pernis apivorus), also known as the pern or common pern,[2] is a bird of prey in the family Accipitridae.

Taxonomy

[edit]The European honey buzzard was formally described in 1758 by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae. He placed it with the falcons and eagles in the genus Falco and coined the binomial name Falco apivorus.[3][4] Linnaeus cited earlier works including the 1678 description by the English naturalist Francis Willughby and the 1713 description by John Ray.[5][6] The European honey buzzard is now one of four species placed in the genus Pernis that was introduced by Georges Cuvier in 1816.[7] The species is monotypic: no subspecies are recognised.[7] The binomen is derived from Ancient Greek pernes πέρνης, a term used by Aristotle for a bird of prey, and Latin apivorus "bee-eating", from apis, "bee" and -vorus, "-eating".[8] In fact, bees are much less important than wasps in the birds' diet. Note that it is accordingly called Wespenbussard ("wasp buzzard") in German and similarly in some other Germanic languages and also in Hungarian ("darázsölyv").

Despite its English name, this species is more closely related to kites of the genera Leptodon and Chondrohierax than to true buzzards in Buteo.[9]

Description

[edit]

The 52–60-centimetre (20–24 in)-long honey buzzard is larger and longer winged, with a 135–150-centimetre (53–59 in) wingspan, when compared to the smaller common buzzard (Buteo buteo). It appears longer necked with a small head, and soars on flat wings. It has a longer tail, which has fewer bars than the Buteo buzzard, usually with two narrow dark bars and a broad dark subterminal bar. The sexes can be distinguished on plumage, which is unusual for a large bird of prey. The male has a blue-grey head, while the female's head is brown. The female is slightly larger and darker than the male.

The soaring jizz is quite diagnostic; the wings are held straight with the wing tips horizontal or sometimes slightly pointed down. The head protrudes forwards with a slight kink downwards and sometimes a very angular chest can be seen, similar to a sparrowhawk, although this may not be diagnostic. The angular chest is most pronounced when seen in direct flight with tail narrowed. The call is a clear peee-lu.

Distribution and habitat

[edit]The European honey buzzard is a summer migrant to a relatively small area in the western Palearctic from most of Europe to as far east as southwestern Siberia. The eastern area boundary is not yet known exactly, it is thought to be in the Tomsk–Novosibirsk–Barnaul area. It is seen in a wide range of habitats, but generally prefers woodland and exotic plantations. It migrates to tropical Africa for European winters.

Movements

[edit]Being a long-distance migrant, the honey buzzard relies on magnetic orientation to find its way south, as well as a visual memory of remarkable geographical features such as mountain ranges and rivers, along the way. It avoids large expanses of water over which it cannot soar. Accordingly, great numbers of honey buzzards can be seen crossing the Mediterranean Sea over its narrowest stretches, such as the Gibraltar Strait, the Messina Strait, the Bosphorus, Lebanon, or in Israel.[11][12]

Status in Britain

[edit]The bird is an uncommon breeder in, and a scarce though increasing migrant to, Britain. Its most well-known summer population is in the New Forest (Hampshire) but it is also found in the Tyne Valley (Northumberland), Wareham Forest (Dorset), Swanton Novers Great Wood (Norfolk), the Neath Valleys (South Wales), the Clumber Park area (Nottinghamshire), near Wykeham Forest (North Yorkshire), Haldon Forest Park (Devon) and elsewhere.[citation needed]

Mimicry

[edit]The similarity in plumage between juvenile European honey buzzard and common buzzard may have arisen as a partial protection against predation by Eurasian goshawks. Although that formidable predator is capable of killing both species, it is likely to be more cautious about attacking the better protected Buteo species, with its stronger bill and talons. Similar Batesian mimicry is shown by the Asian Pernis species, which resemble the Spizaetus hawk-eagles.[13]

Behaviour

[edit]It is sometimes seen soaring in thermals. When flying in wooded vegetation, honey buzzards usually fly quite low and perch in midcanopy, holding the body relatively horizontal with its tail drooping. The bird also hops from branch to branch, each time flapping its wings once, and so emitting a loud clap. The bird often appears restless with much ruffling of the wings and shifting around on its perch. The honey buzzard often inspects possible locations of food from its perch, cocking its head this way and that to get a good look at possible food locations. This behaviour is reminiscent of an inquisitive parrot.

Breeding

[edit]

The honey buzzard breeds in woodland, and is inconspicuous except in the spring, when the mating display includes wing-clapping. Breeding males are fiercely territorial. The clutch typically consists of two eggs, less often one or three. Siblicide is rarely observed.[15]

Feeding

[edit]It is a specialist feeder, living mainly on the larvae and nests of wasps and hornets, although it will take small mammals, reptiles, and birds. It is the only known predator of the Asian hornet.[16] It spends large amounts of time on the forest floor excavating wasp nests. It is equipped with long toes and claws adapted to raking and digging, and scale-like feathering on its head, thought to be a defence against the stings of its prey.[17] Honey buzzards are thought to have a chemical deterrent in their feathers that protects them from wasp attacks.[18]

In culture

[edit]The honey buzzard was historically considered a winter delicacy in Europe, with 19th century texts stating it was frequently caught in winter and described as "fat and delicious eating".[19]

References

[edit]- ^ BirdLife International. (2021). "Pernis apivorus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021: e.T22694989A206749274. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-3.RLTS.T22694989A206749274.en. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ Georges Cuvier, Edward Blyth, Robert Mudie, George Johnston, John Obadiah Westwood, William Benjamin Carpenter, The Animal Kingdom: Arranged After Its Organization, Forming a Natural History of Animals, and an Introduction to Comparative Anatomy, 1851, p. 171

- ^ Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 91.

- ^ Mayr, Ernst; Cottrell, G. William, eds. (1979). Check-List of Birds of the World. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Museum of Comparative Zoology. p. 287.

- ^ Willughby, Francis (1678). Ray, John (ed.). The Ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the County of Warwick. London: John Martyn. p. 21, Plate 3.

- ^ Ray, John (1713). Synopsis methodica avium & piscium (in Latin). Vol. Avium. London: William Innys. p. 16.

- ^ a b Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (December 2023). "Hoatzin, New World vultures, Secretarybird, raptors". IOC World Bird List Version 14.1. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 8 March 2024.

- ^ Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 51, 298. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ Catanach, T.A.; Halley, M.R.; Pirro, S. (15 July 2023). "Enigmas no longer: using ultraconserved elements to place several unusual hawk taxa and address the non-monophyly of the genus Accipiter (Accipitriformes: Accipitridae)". bioRxiv. doi:10.1101/2023.07.13.548898. Retrieved 8 March 2024.

- ^ a b Ferguson-Lees, J.; Christie, D.A. (2001) Raptors of the World. Christopher Helm, London.

- ^ Garcia, Ernest F.J.; Bensusan, Keith J. (November 2006). "Northbound migrant raptors in June and July at the Strait of Gibraltar" (PDF). British Birds. 99: 569–575.

- ^ Zalles, Jorje I.; Bildstein, Keith L. (2000). Birdlife International (ed.). Raptor watch: a global directory of raptor migration sites.

- ^ Duff, Daniel (March 2006). "Has the juvenile plumage of Honey-buzzard evolved to mimic that of Common Buzzard?" (PDF). British Birds. 99: 118–128.

- ^ Perrins, Christopher M.; Attenborough, David (1987). New generation guide to the birds of Britain and Europe (1st University of Texas Press ed.). Austin: University of Texas Press. p. 92. ISBN 9780292755321.

- ^ a b van Manen, Willem (2013). "Biologie van Wespendieven Pernis apivorus in het oerbos Bialowiza". De Takkeling. 21 (2): 101–126. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- ^ "European Honey Buzzards prey on invasive hornets". 18 October 2019. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ Cocker, Mark; Mabey, Richard (2005). Birds Britannica. London: Chatto & Windus. pp. 113–114. ISBN 0-7011-6907-9.

- ^ Sievwright, H (2016). "The feather structure of Oriental honey buzzards (Pernis ptilorhynchus) and other hawk species in relation to their foraging behavior". Zoological Science. 33 (3): 295–302. doi:10.2108/zs150175. PMID 27268984. S2CID 21903642.

- ^ Bewick, T. (1809). "The Honey Buzzard". A history of British birds : the figures engraved on wood. Newcastle: Edward Walker, for T. Bewick. pp. 59–64.

- Gensbøl, Benny (1989). Collins guide to the Birds of Prey of Britain and Europe North Africa and the Middle East. William Collins Sons and Co Ltd. ISBN 0-00-219176-8.

External links

[edit]- (European) honey buzzard species text in The Atlas of Southern African Birds

- Ageing and sexing (PDF; 5.4 MB) by Javier Blasco Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze

- European Honey-Buzzard Text, map, photographs and audio at Oiseaux.net

- Honey-buzzard in Britain Identification, calls, movements.

- BirdLife species factsheet for Pernis apivorus

- "Pernis apivorus". Avibase.

- "Western Honey-buzzard media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Eurasian Honey-Buzzard photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Audio recordings of European honey buzzard on Xeno-canto.