Hans von Luck

Hans von Luck | |

|---|---|

Oberstleutnant Hans von Luck 1944 | |

| Born | 15 July 1911 Flensburg, German Empire |

| Died | 1 August 1997 (aged 86) Hamburg, Germany |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | Army |

| Years of service | 1929–45 |

| Rank | Oberst |

| Unit | 7th Panzer-Division 21st Panzer-Division |

| Battles / wars | |

| Awards | Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross |

| Spouse(s) | Regina von Luck |

| Other work | Military lecturer, author |

Hans–Ulrich Freiherr von Luck und Witten (15 July 1911 – 1 August 1997), usually shortened to Hans von Luck, was a German officer in the Wehrmacht of Nazi Germany during World War II. Von Luck served with the 7th Panzer Division and 21st Panzer Division. Von Luck is the author of the book Panzer Commander.

Early life and interwar period

[edit]Luck was born in Flensburg, into a Prussian family with old military roots. Luck's father, Otto von Luck, served in the Imperial German Navy and died in July 1918 of an influenza virus. His mother remarried a Reichsmarine Chaplain. In 1929, Luck joined the Reichswehr (army). Through the winter of 1931−1932, Luck attended a nine-month course for officer cadets, led by then Captain Erwin Rommel, at the infantry school in Dresden.[1] On 30 June 1934 Luck's unit took part in the Night of the Long Knives, arresting several Sturmabteilung (SA) members in Stettin.[2] In 1939 Luck was posted to the 2nd Light Division, serving in its armoured reconnaissance battalion.

World War II

[edit]Invasions of Poland and France

[edit]

On 1 September 1939 the 2nd Light Division, under General Georg Stumme, participated in the invasion of Poland. Luck served as a company commander in the division's reconnaissance battalion.[3] The division was reorganized and reequipped to form the 7th Panzer Division, with Rommel assuming command on 6 February 1940. Luck served as a company commander in an armoured reconnaissance battalion.[4]

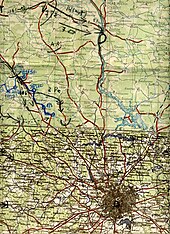

The 7th Panzer Division was a part of the XV Army Corps under General Hermann Hoth in Army Group A. On 10 May 1940, the division participated in the invasion of France. Luck's reconnaissance battalion led the division's advance into Belgium, reaching the Meuse in three days.[5] In his memoir Luck describes the division's crossing of the Meuse and Rommel's active role in gaining the crossing.[6] On 28 May, Luck was appointed commander of the reconnaissance battalion.[7] Luck's unit advanced through Rouen, Fecamp, and Cherbourg. In February 1941 Rommel was replaced by General Freiherr von Funk, and in June Luck moved with his division to East Prussia in preparation for the invasion of the Soviet Union.[citation needed]

Invasion of the Soviet Union

[edit]

Luck was made Hauptmann and attached to the 7th Panzer Division's headquarters staff.[8] His division was a part of the 3rd Panzer Group of Army Group Center.[9] In this capacity he participated in the Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union. The 7th Panzer Division spearheaded the 3rd Panzer Group as it drove east and captured Vilnius in Lithuania, before driving on Minsk to form the northern inner encirclement arm of the Bialystok-Minsk pocket.[9] Following the capture of Minsk the armoured group continued east towards Vitebsk.[9] At Vitebsk, Luck was assigned as commander of the division's reconnaissance battalion.[10]

The division participated in creating the large pocket around Smolensk, cutting the Smolensk–Moscow road.[9] Luck and his unit continued on towards Moscow. In his memoirs, he describes the stiffening Soviet resistance and problems the German forces faced relating to weather and road conditions.[11] Since November Rommel had requested Luck be transferred to Africa to take over command of one of his reconnaissance battalions.[1] The transfer was approved in late January once the crisis of the Soviet winter offensive had passed.[12]

North Africa

[edit]Luck was promoted to major, spending February and March 1942 on leave. Reporting back for duty on 1 April 1942, he reached Africa on 8 April and assumed command over the 3rd Panzer Reconnaissance Battalion of the 21st Panzer Division.[13][14] Luck spent June to mid-September in Germany, recuperating from a combat wound. Returning to Africa, he resumed command of the 3rd Reconnaissance Battalion.[15]

On 23 October 1942, the British launched the attack of the Second Battle of El Alamein.[16] The Axis position deteriorated leading to a retreat. Luck was one of Rommel's most experienced commanders, and he called upon Luck's reconnaissance battalion to screen his withdrawal.[17] By December the Axis forces had retreated to Tripoli. On 6 May the forces in Africa surrendered, with more than 130,000 Germans taken prisoner. By that time Luck was in Germany.

The Normandy invasion

[edit]

After North Africa and leave in Berlin, Luck was assigned in August 1943 as an instructor at a panzer reconnaissance school in Paris. In March 1944 he was to be appointed as commander of a panzer regiment in the new Panzer Lehr Division in France under Fritz Bayerlein. However, in mid-April he was told by Bayerlein that as Feuchtinger apparently had more influence at Headquarters he was to serve under Feuchtinger.[18]

Luck was assigned to the 21st Panzer Division, stationed in Brittany and commanded by Edgar Feuchtinger. In early May, Luck was placed in command of the 125th Panzer Grenadier Regiment.[19][20] Luck's regiment was stationed at Vimont, southeast of Caen, with two companies of assault guns in support.

On 6 June 1944, the invasion of Normandy started. During the night Luck was startled by the reports of paratroopers landing in his area, and establishing a bridgehead on the east side of the Orne River. Luck requested permission to attack, but Feuchtinger, the 21st Panzer Division's commander, refused to allow him to do so, citing strict orders not to engage in major operations unless cleared to do so by the high command.[21] Apart from an order at 4:30 a.m. directing other elements of the division to move against the paratroopers of the British 6th Airborne Division, the 21 Panzer Division remained mostly motionless. As the morning wore on, the defenders on the coast were overcome and the British beachheads secured.

Around 10:30 a.m. General Erich Marcks, commander of the German LXXXIV Corps to which the 21st Panzer Division was attached, ordered the entire 21st to leave a single company from the division's 22nd Panzer Regiment to deal with the paratroopers and move the rest of the division to attack the British forces advancing from the beachhead toward Caen.[22] Feuchtinger finally ordered his division forward, leaving a company of panzers as ordered, but also leaving Luck's 125 Panzergrenadier Regiment. This order was later countermanded, this time from 7th Army, and only Luck's detachment was left to attack the paratroopers east of Orne. The confusion and inflexibility of the German command situation markedly delayed the German response. Nevertheless, at 1700 p.m. Luck attempted to break through to the Orne river bridges at Bénouville with his armoured personnel carriers, but heavy fire from the warships supporting the British paratroopers, under Major John Howard, holding the bridges drove his forces back.[23] Added to this, more British paratroopers landed in the rear area of the regiment, causing some of Luck's forces to fall back.

On the morning of 9 June Luck's command was designated Kampfgruppe von Luck, and in addition to the elements of the 125th Panzer Grenadier Regiment already under Luck's command, it consisted of a battalion, three assault-gun batteries and one antitank company with 88mm guns. With this force, Luck was tasked with assaulting the Orne bridges, and recapturing them from the British paratroopers. Starting one hour before dawn to avoid the worst of the British naval and aerial support, the Kampfgruppe advanced on the village of Ranville, dislodging the enemy there, but it could not penetrate the British lines to reach the bridges. The British paratroopers, reinforced by the British 51st (Highland) Division and the 4th Armoured Brigade, then attempted to advance around the eastern edge of Caen as the left side of an envelopment attack, but their efforts were thwarted by Luck's unit.[24] Over the next several days Luck's group initiated what amounted to a spoiling attack, tying up the British units. On 12 June Kampfgruppe von Luck engaged in the fighting for the village of Sainte-Honorine, lying on a hill overlooking the invasion beaches.[25] The British forces east of the Orne were unable to move forward until 16 June.[24]

Operation Goodwood

[edit]At the beginning of July, the area defended by Luck's Kampfgruppe came under the control of I SS Panzer Corps under the command of Obergruppenführer Sepp Dietrich. Nearby was the Heavy Tank Battalion 503 equipped with one company of Tiger II tanks and two companies of Tiger I tanks. On 18 July, Field Marshall Bernard Montgomery launched Operation Goodwood; an operation aimed to wear down the German armoured forces in Normandy in addition to seizing territory, on the eastern flank of Caen, to the extent of the Bourguébus–Vimont–Bretteville area. If successful, the British hoped to follow this limited attack by pushing reconnaissance forces south towards Falaise.[26][27][28] The offensive opened with a massive aerial bombardment, followed by artillery and naval gunfire, intended to suppress or destroy all defences in the path of the attack.[29]

During the morning, Luck had just returned from a three-day leave in Paris. Informed of the air raids, he moved forward to determine the exact situation and soon realized that a major offensive was underway.[30][31] The air raid had neutralized the remnants of the 16th Luftwaffe Field Division, which held the front line, as well as elements of the 21st Panzer Division (in particular, elements of the 22nd Panzer Battalion and the 1st battery of Assault Gun Battalion 200) leaving a hole in the German defensive line.[32][33] While elements of the advancing British 11th Armoured Division were held up in an engagement with self-propelled guns of the 200th Assault Gun Battalion, the 2nd Fife and Forfar Yeomanry advanced past Cagny. As the regiment did, they came under heavy anti-tank fire resulting in the loss of four tanks.[34][35][36]

After the war, Luck wrote that he was responsible for this barrage of anti-tank fire, saying that he used his sidearm to threaten a Luftwaffe officer into action, to fire upon the advancing tanks with 88 mm flak guns.[37] Luck's account has been widely repeated,[35][38] although competing theories have also been suggested: The British 8 Corps history states that German anti-tank guns based in Soliers, which had escaped the aerial bombardment, were responsible.[39]

Ian Daglish, critical of Luck's account, stated "there turns out to be surprisingly little" evidence to support Luck's version of events, and that all accounts of 88 mm flak guns in Cagny being used in an anti-tank capacity "can be traced directly to Luck and no one else." He further wrote that neither the commander of the 200th Assault Gun Battalion nor the commander of Luftwaffe flak guns made any comment in regards to this action and that based on locations of flak positions, it was illogical for a heavy flak battery to have been located there.[40] Daglish also wrote that Luck's account of the placement of the guns "is imprecise" and "expert analysis of aerial photographs of the area taken at midday ... reveals no trace of [the battery] nor of any towing vehicles or their distinctive tracks". Such weapons and vehicles "could not be hidden within a mere couple of hours of relocation".[41] Daglish argued that Luck embellished his role during post-war official British tours of the battlefield, with his version of events eventually coming into question (off the record).[42] Daglish wrote that elements of the 200th Assault Gun Battalion were in the area and that any number of German anti-tank guns could have fired on the 2nd Fife and Forfar and that 88 mm anti-tank guns were deployed to the Cagny area throughout the day.[43] John Buckley is also critical of Luck's account, and called it "colourful and enthralling". He argued that despite there being "no doubt that heavy anti-tank gunfire from in and around Cagny began to account for British tanks", no evidence that the Luftwaffe had guns in Cagny at the time given the dispositions of other Luftwaffe batteries. Buckley wrote that Luck had embroidered his role.[37]

Stephen Napier reassessed these criticisms of Luck's account. He wrote that "heavy anti-aircraft guns were located in the outlying villages of Caen" and "photographic evidence of the Luftwaffe batteries in the area exists", in addition the wreckage of three 88mm guns was found by the Guards division that afternoon in Cagny, which would corroborate Luck's claim to have ordered the destruction of the guns upon abandoning Cagny.[44] Napier wrote that Luck's account of threatening a Luftwaffe officer is plausible given that "88mm anti-aircraft crews did not expect to become embroiled in fighting as per III Flak Korps policy, and their direct involvement occasionally took some persuasion."[44] Napier also asserts that the timeline of Luck's stated confrontation with the Luftwaffe battery commander, just after 09:00 hours, correlates with the losses the 2nd Fife and Forfar Yeomanry at 09:30 hours since a "88mm flak battery would only need about 15 minutes to relocate a short distance".[45] Napier further writes that the fact that two Tiger tanks were destroyed by German friendly fire "suggests the actions of an inexperienced Luftwaffe crew" unable to identify retreating German tanks.[44] According to Napier the 75mm Pak 40 anti-tank guns were incapable of the clean armour penetrations found on the Tigers at that range and the only other alternative unit that could have engaged the British tanks was Becker's 4th Battery located in Le Mensnil Frementel. Napier notes "if this company did not move before 0930 hours, it would have been cut off when the leading tanks of the 29th brigade crossed the railway" and reasoned "since the battery "Was able to relocate successfully to just south of Four where it was in action for the rest of the day and so must have moved well before 0930 hours."[44] Napier stated that an officer of the 2nd Fife and Forfar wrote in his memoirs "of his surprise at seeing a German officer in dress uniform surveying the battlefield from Cagny".[44] Napier concluded that Luck "correctly attributed credit where it was due and his only sin is the assumption of a mantle previously worn by Rommel who stopped the British tank attack at Arras in 1940 by ordering the 88mm flak guns to engage the ground targets of the British tank forces."[46]

Luck spent the rest of the day using the resources he had to check the gaps in the line. In the afternoon, the first elements of the 1st SS Division Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler had moved up in support and the situation was somewhat stabilized. The following day, Luck's Kampfgruppe, supported by the armour of the 1st SS, held the British in check, and launched counterattacks on the British flanks. The British attack ended on 20 July.[47] In the evening, the 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend relieved Luck's men. For his service during Operation Goodwood, Luck was awarded the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross, and on 8 August, he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel.

The Falaise Pocket and Retreat to Germany

[edit]A week later, after a brief rest and refit, the 21st Panzer Division was sent to the Villers-Bocage area south of Bayeux. On 26 July Panzer Lehr's lines were broken, and the 21st Panzer Division reoriented themselves on this new threat. On 31 July General Patton's forces broke through at Avranches into open country.[48] The German motorized forces were brought west to counterattack in an effort to cut the supply and communication lines of the advancing American forces, but the counterattack was known due to Ultra decrypts and the attacking formations were heavily shelled and bombarded, stopping the attack before it could jump off.[49] Unable to check the advancing American armour, all the German divisions in Normandy were in danger of being encircled.[50]

Luck reached Falaise after two weeks of delaying action. On 17 August a British attack split the 21st Panzer Division, leaving half inside the now emerging Falaise Pocket, while Luck's command found itself on the outside. Kampfgruppe von Luck was now tasked with holding the Western end of the gap open, which it did until 21 August. About half of the 100,000 trapped troops managed to escape, though most of the heavy materiel and vehicles were destroyed in the pocket. A new threat was already emerging, with Patton threatening to create yet another pocket, south of the Seine River. Luck was put in command of the remains of 21st Panzer Division.[citation needed]

The Defence of Germany

[edit]On 9 September, Luck's command reached Strasbourg, where it was attached to General Hasso von Manteuffel's Fifth Panzer Army. During the Battle of Dompaire which was fought a few days later, the 112 Panzer Brigade suffered heavy tank losses. Luck attempted to salvage a desperate situation but ended up having to retreat in order to conserve his forces. In January 1945, when the division was moved to the Oder front, the division took part in fighting along the Reitwein Spur. Luck surrendered to the Soviet forces while attempting a breakout from the Halbe pocket on 27 April 1945.[citation needed]

After the war

[edit]After the war, Luck was interned at GUPVI forced labour camp 518/I in Tkibuli, Georgia, a camp for POWs and internees, similar to a GULAG camp.[51] He was released in December 1949 and returned to West Germany.[52] He became involved in veterans' associations and was frequently asked to lecture at military schools. He spoke annually for the British Staff College during their summer tours of the Normandy battlefields, and subsequently was asked to speak at a number of other military seminars.[53] He was a participant in the UK's Ministry of Defence Army Department film presentation on Operation Goodwood Lectures.[54]

Through his involvement as a speaker at military lectures he came to be good friends with several of his former adversaries, including Brigadier David Stileman, Major Alastair Morrison of the 4th/7th Royal Dragoon Guards, and Major John Howard of the British 6th Airborne Division.[53] He also formed a friendship with popular historian Stephen Ambrose, who encouraged him to write his memoirs, which was titled Panzer Commander.

Hans von Luck died in Hamburg on 1 August 1997 at the age of 86.[55]

Awards

[edit]- German Cross in Gold on 2 January 1942 as Hauptmann in Kradschützen-Bataillon 7[56]

- Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross on 8 August 1944 as Major and leader of Panzergrenadier-Regiment 125[57]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Butler 2015, p. 393.

- ^ Luck 1989, p. 9−16.

- ^ Luck 1989, p. 32.

- ^ Luck 1989, p. 37.

- ^ Deighton 1980, p. 211.

- ^ Luck 1989, p. 38.

- ^ Luck 1989, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Luck 1989, p. 66.

- ^ a b c d Askey 2013, p. 379.

- ^ Luck 1989, p. 70.

- ^ Luck 1989, p. 76.

- ^ Luck 1989, pp. 77–83.

- ^ Fraser 1993, p. 389.

- ^ Butler 2015, p. 392.

- ^ Luck 1989, p. 110.

- ^ Lewin 1998, p. 173.

- ^ Fraser 1993, p. 413.

- ^ Margaritis, Peter (2019). Countdown to D-Day: The German perspective. Oxford, UK & PA, USA: Casemate. pp. 319–321. ISBN 978-1-61200-769-4.

- ^ Luck 1989, p. 167.

- ^ Keegan 1982, p. 202.

- ^ Mitcham 1983, p. 82.

- ^ Mitcham 1983, p. 83.

- ^ Ambrose, D-Day

- ^ a b Mitcham 1983, p. 103.

- ^ Luck 1989, p. 187.

- ^ Jackson 2006, p. 79.

- ^ Trew, p. 66

- ^ Ellis, pp. 330–331

- ^ Keegan 1982, p. 193.

- ^ Luck 1989, pp. 187, 192.

- ^ Keegan 1982, pp. 205–206.

- ^ Luck 1989, p. 192.

- ^ Keegan 1982, p. 205.

- ^ Dunphie, p. 74

- ^ a b Trew, p. 80

- ^ Napier, p. 249

- ^ a b Buckley (2013), p. 105

- ^ D'Este, p. 375

- ^ Jackson, p. 98

- ^ Daglish, pp. 255, 258–261

- ^ Daglish, p. 256

- ^ Daglish, p. 258

- ^ Daglish, pp. 260 186

- ^ a b c d e Napier (2015), p. 250

- ^ Napier (2015), p. 249

- ^ Napier (2015), p. 248-251

- ^ Keegan 1982, p. 216.

- ^ Hastings 2006, p. 260.

- ^ Hastings 2006, p. 262.

- ^ Hastings 2006, p. 263.

- ^ Karner, Stefan, Im Archipel GUPVI. Kriegsgefangenschaft und Internierung in der Sowjetunion 1941-1956. Wien-München 1995. ISBN 978-3-486-56119-7 (book review, English) (in German)

- Russian translation: 2002, ISBN 5-7281-0424-X

- ^ Luck 1989, p. 328.

- ^ a b "Obituary Brigadier David Stileman". The Times. 10 August 2011. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- ^ Ministry of Defense; Army Department: Operation Goodwood

- ^ Mitcham 2009, p. xcvii.

- ^ Patzwall & Scherzer 2001, p. 286.

- ^ Scherzer 2007, p. 516.

Bibliography

[edit]- Ambrose, Stephen E (1994). D-Day, June 6, 1944, The Battle for the Normandy beaches, Pocket Books. ISBN 0-7434-4974-6

- Ambrose, Stephen E (2001). Pegasus Bridge. Touchstone Books. ISBN 0-671-67156-1.

- Askey, Nigel (2013). Operation Barbarossa: the complete organisational and statistical analysis, and military simulation. Lulu Publishing.

- Biess, Frank (2006). Homecomings : returning POWs and the legacies of defeat in postwar Germany. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

- Butler, Daniel Allen (2015). Field Marshal: The Life and Death of Erwin Rommel. Havertown, PA; Oxford: Casemate. ISBN 978-1-61200-297-2.

- Daglish, Ian (2005). Goodwood. Over the Battlefield. Leo Cooper. ISBN 1-84415-153-0.

- Deighton, Len (1980). Blitzkrieg: From the Rise of Hitler to the Fall of Dunkirk. New York: Knopf, Distributed by Random House.

- Dunphie, Chris (2005). The Pendulum of Battle: Operation Goodwood - July 1944. MLRS Books. ISBN 978-1-844-15278-0.

- Ellis, Major L. F.; with Allen RN, Captain G. R. G. Allen; Warhurst, Lieutenant-Colonel A. E. & Robb, Air Chief-Marshal Sir James (2004) [1st. pub. HMSO 1962]. Butler, J. R. M. (ed.). Victory in the West: The Battle of Normandy. History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. I. Naval & Military Press. ISBN 1-84574-058-0.

- Fraser, David (1993). Knight's Cross: A Life of Field Marshal Erwin Rommel. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-018222-9.

- Hastings, Max (2006) [1985]. Overlord: D-Day and the Battle for Normandy. Vintage Books USA; Reprint edition. ISBN 0-307-27571-X.

- Jackson, G. S. (2006) [1945]. 8 Corps: Normandy to the Baltic. MLRS Books. ISBN 978-1-905696-25-3.

- Keegan, John (1982). Six Armies in Normandy: from D-Day to the liberation of Paris, June 6th-August 25th, 1944. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 0-14-02-3542-6.

- Luck, Hans von (1989). Panzer Commander: The Memoirs of Colonel Hans von Luck. New York: Dell Publishing of Random House. ISBN 0-440-20802-5.

- Luck, Hans von (1991). Panzer Commander: The Memoirs of Colonel Hans von Luck. Dell Publishing. ISBN 0-440-20802-5.

- Lewin, Ronald (1998) [1968]. Rommel As Military Commander. New York: B&N Books. ISBN 978-0-7607-0861-3.

- Mitcham, Samuel W (2009). Defenders of Fortress Europe. Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books. ISBN 978-1-59797-274-1.

- Mitcham, Samuel W (1983). Rommel's last battle : the Desert Fox and the Normandy campaign. New York: Stein and Day.

- Napier, Stephen (2015). The Armoured Campaign in Normandy June-August 1944. The History Press. pp. 248–251. ISBN 9780750964739.

- Patzwall, Klaus D.; Scherzer, Veit (2001). Das Deutsche Kreuz 1941 – 1945 Geschichte und Inhaber Band II [The German Cross 1941 – 1945 History and Recipients Volume 2] (in German). Norderstedt, Germany: Verlag Klaus D. Patzwall. ISBN 978-3-931533-45-8.

- Scherzer, Veit (2007). Die Ritterkreuzträger 1939–1945 Die Inhaber des Ritterkreuzes des Eisernen Kreuzes 1939 von Heer, Luftwaffe, Kriegsmarine, Waffen-SS, Volkssturm sowie mit Deutschland verbündeter Streitkräfte nach den Unterlagen des Bundesarchives [The Knight's Cross Bearers 1939–1945 The Holders of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross 1939 by Army, Air Force, Navy, Waffen-SS, Volkssturm and Allied Forces with Germany According to the Documents of the Federal Archives] (in German). Jena, Germany: Scherzers Militaer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-938845-17-2.

- Trew, Simon; Badsey, Stephen (2004). Battle for Caen. Battle Zone Normandy. Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-7509-3010-1.

External links

[edit]- 1911 births

- 1997 deaths

- People from Flensburg

- Military personnel from the Province of Schleswig-Holstein

- German barons

- Recipients of the Gold German Cross

- Recipients of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross

- German prisoners of war in World War II held by the Soviet Union

- Recipients of the Silver Medal of Military Valor

- German Army officers of World War II

- Military personnel from Schleswig-Holstein

- Panzer commanders