Sinking of the Titanic

A request that this article title be changed to Sinking of the RMS Titanic is under discussion. Please do not move this article until the discussion is closed. |

The sinking of the Titanic depicted in Untergang der Titanic, a 1912 illustration by Willy Stöwer | |

| Date | 14–15 April 1912 |

|---|---|

| Time | 23:40–02:20 (02:38–05:18 GMT)[a] |

| Duration | 2 hours and 40 minutes |

| Location | North Atlantic Ocean, 370 miles (600 km) southeast of Newfoundland |

| Coordinates | 41°43′32″N 49°56′49″W / 41.72556°N 49.94694°W |

| Type | Maritime disaster |

| Cause | Collision with an iceberg on 14 April |

| Participants | Titanic crew and passengers |

| Outcome | Maritime policy changes; SOLAS |

| Deaths | 1,490–1,635 |

RMS Titanic sank on 15 April 1912 in the North Atlantic Ocean. The largest ocean liner in service at the time, Titanic was four days into her maiden voyage from Southampton to New York City, with an estimated 2,224 people on board when she struck an iceberg at 23:40 (ship's time)[a] on 14 April. Her sinking two hours and forty minutes later at 02:20 ship's time (05:18 GMT) on 15 April resulted in the deaths of more than 1,500 people, making it one of the deadliest peacetime maritime disasters in history.

Titanic received six warnings of sea ice on 14 April but was travelling at a speed of roughly 22 knots (41 km/h) when her lookouts sighted the iceberg. Unable to turn quickly enough, the ship suffered a glancing blow that buckled her starboard side and opened six of her sixteen compartments to the sea. Titanic had been designed to stay afloat with up to four of her forward compartments flooded, and the crew used distress flares and radio (wireless) messages to attract help as the passengers were put into lifeboats. In accordance with existing practice, the Titanic's lifeboat system was designed to ferry passengers to nearby rescue vessels, not to hold everyone on board simultaneously; therefore, with the ship sinking rapidly and help still hours away, there was no safe refuge for many of the passengers and crew with only twenty lifeboats, including four collapsible lifeboats. Poor preparation for and management of the evacuation meant many boats were launched before they were completely full.

Titanic sank with over a thousand passengers and crew still on board. Almost all of those who ended up in the water died within minutes due to the effects of cold shock and incapacitation. RMS Carpathia arrived about an hour and a half after the sinking and rescued all of the 710 survivors by 09:15 on 15 April. The disaster shocked the world and caused widespread outrage over the lack of lifeboats, lax regulations, and the unequal treatment of third-class passengers during the evacuation. Subsequent inquiries recommended sweeping changes to maritime regulations, leading to the establishment in 1914 of the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) which still governs maritime safety today.

Background

At the time of her entry into service on 2 April 1912, the Titanic was the second of three[b] Olympic-class ocean liners, and was the largest ship in the world. She and the earlier RMS Olympic were almost one and a half times the gross register tonnage of Cunard's RMS Lusitania and RMS Mauretania, the previous record holders, and were nearly 100 feet (30 m) longer.[2] The Titanic could carry 3,547 people in speed and comfort,[3] and was built on an unprecedented scale. Her reciprocating engines were the largest that had ever been built, standing 40 feet (12 m) high and with cylinders 9 feet (2.7 m) in diameter requiring the burning of 600 long tons (610 t) of coal per day.[3]

The passenger accommodation, especially the first class section, was said to be "of unrivalled extent and magnificence",[4] indicated by the fares that first class accommodation commanded. The Parlour Suites (the most expensive and most luxurious suites on the ship) with private promenade cost over $4,350 (equivalent to $137,000 today)[5] for a one-way transatlantic passage. Even third class, though considerably less luxurious than second and first classes, was unusually comfortable by contemporary standards and was supplied with plentiful quantities of good food, providing her passengers with better conditions than many of them had experienced at home.[4]

The Titanic's maiden voyage began shortly after noon on 10 April 1912 when she left Southampton on the first leg of her journey to New York.[6] An accident was narrowly averted only a few minutes later, as the Titanic passed the moored liners SS City of New York of the American Line and Oceanic of the White Star Line, the latter of which would have been her running mate on the service from Southampton. Her huge displacement caused both of the smaller ships to be lifted by a bulge of water and then dropped into a trough. New York's mooring cables could not take the sudden strain and snapped, swinging her around stern-first towards the Titanic. A nearby tugboat, Vulcan, came to the rescue by taking New York under tow, and Titanic's 62-year-old Captain Edward Smith, the most senior of the White Star Line's captains, ordered her engines to be put "full astern".[7] The two ships avoided a collision by a distance of about 4 feet (1.2 m). The incident, as well as a subsequent stop to offload a few stragglers by tug, delayed the Titanic's departure by at most three-quarters of an hour, while the drifting New York was brought under control.[8]

A few hours later, the Titanic called at Cherbourg Harbour in north-western France, a journey of 80 nautical miles (148 km; 92 mi), where she took on passengers.[9] Her next port of call was Queenstown (now Cobh) in Ireland, which she reached around midday on 11 April.[10] She left in the afternoon after taking on more passengers and stores.[11]

By the time the Titanic departed westwards across the Atlantic, she was carrying 892 crew members and 1,320 passengers. This was only about half of her full passenger capacity of 2,435,[12] as it was the low season and shipping from the UK had been disrupted by a coal miners' strike.[13] Her passengers were a cross-section of Edwardian society, from millionaires such as John Jacob Astor and Benjamin Guggenheim,[14] to poor emigrants from countries as disparate as Armenia, Ireland, Italy, Sweden, Syria and Russia seeking a new life in the United States.[15]

Captain Smith had four decades of seafaring experience and had served as captain of RMS Olympic, from which he was transferred to command the Titanic.[16] The vast majority of the crew who served under him were not trained sailors, but were either engineers, firemen, or stokers, responsible for looking after the engines; or stewards and galley staff, responsible for the passengers. The six watch officers and 39 able seamen constituted only around five percent of the crew,[12] with the majority having been taken on at Southampton, and as a result lacked the time to familiarise themselves with the ship.[17]

The ice conditions were attributed to a mild winter that caused large numbers of icebergs to shift off the west coast of Greenland.[18]

A fire had begun in one of the Titanic's coal bins approximately 10 days before the ship's departure and continued to burn for several days into the voyage, but it was extinguished on 13 April.[19][20] The weather improved significantly during the day, from brisk winds and moderate seas in the morning to a crystal-clear calm by evening, as the ship's path took her beneath an arctic high-pressure system.[21]

14 April 1912

Iceberg warnings

On 14 April 1912, Titanic's radio operators[c] received six messages from other ships warning of drifting ice, which passengers on Titanic had begun to notice during the afternoon. The ice conditions in the North Atlantic were the worst of any April in the previous 50 years (which was the reason why the lookouts were unaware that they were about to steam into a line of drifting ice several miles wide and many miles long).[22] The radio operators did not relay all of these messages; at the time, all wireless operators on ocean liners were employees of the Marconi's Wireless Telegraph Company and not members of their ship's crew. As such, their primary responsibility was to send messages for the passengers, with weather reports as a secondary concern.

The first warning came at 09:00 from RMS Caronia reporting "bergs, growlers[d] and field ice".[23] Captain Smith acknowledged receipt of the message. At 13:42, RMS Baltic relayed a report from the Greek ship Athenia that she had been "passing icebergs and large quantities of field ice".[23] Smith also acknowledged this report, and showed it to White Star Line chairman J. Bruce Ismay, aboard Titanic for her maiden voyage.[23] Smith ordered a new course to be set, which would take the ship further south.[24]

At 13:45, the German ship SS Amerika, which was a short distance to the south, reported she had "passed two large icebergs".[25] This message never reached Captain Smith or the other officers on Titanic's bridge. The reason is unclear, but it may have been forgotten because the radio operators had to fix faulty equipment.[25]

SS Californian reported "three large bergs" at 19:30, and at 21:40, the steamer Mesaba reported: "Saw much heavy pack ice and great number large icebergs. Also field ice."[26] This message, too, never left the Titanic's radio room. The radio operator, Jack Phillips, may have failed to grasp its significance because he was preoccupied with transmitting messages for passengers via the relay station at Cape Race, Newfoundland; the radio set had broken down the day before, resulting in a backlog of messages that the two operators were trying to clear.[25] A final warning was received at 22:30 from operator Cyril Evans of Californian, which had halted for the night in an ice field some miles away, but Phillips cut it off and signalled back: "Shut up! Shut up! I'm working Cape Race."[26]

Although the crew was aware of ice in the vicinity, they did not reduce the ship's speed, and continued to steam at 22 knots (41 km/h; 25 mph), only 2 knots (3.7 km/h; 2.3 mph) short of her maximum speed.[25][e] Titanic's high speed in waters where ice had been reported was later criticised as reckless, but it reflected standard maritime practice at the time. According to Fifth Officer Harold Lowe, the custom was "to go ahead and depend upon the lookouts in the crow's nest and the watch on the bridge to pick up the ice in time to avoid hitting it".[28]

The North Atlantic liners prioritised time-keeping above all other considerations, sticking rigidly to a schedule that would guarantee their arrival at an advertised time. They were frequently operated at close to their full speed, treating hazard warnings as advisories rather than calls to action. It was widely believed that ice posed little risk; close calls were not uncommon, and even head-on collisions had not been disastrous. In 1907, SS Kronprinz Wilhelm, a German liner, had rammed an iceberg and suffered a crushed bow, but was still able to complete her voyage. That same year, Titanic's future captain, Edward Smith, declared in an interview that he could not "imagine any condition which would cause a ship to founder. Modern shipbuilding has gone beyond that."[29]

"Iceberg, right ahead!"

Titanic enters Iceberg Alley

As Titanic approached her fatal collision, most passengers had gone to bed, and command of the bridge had passed from Second Officer Charles Lightoller to First Officer William Murdoch. Lookouts Frederick Fleet and Reginald Lee were in the crow's nest, 29 metres (95 ft) above the deck. The air temperature had fallen to near freezing, and the ocean was completely calm. Colonel Archibald Gracie, one of the survivors of the disaster, later wrote that "the sea was like glass, so smooth that the stars were clearly reflected."[30] It is now known that such exceptionally calm water is a sign of nearby pack ice.[31]

Although the air was clear, there was no moon, and with the sea so calm, there was nothing to give away the position of the nearby icebergs; had the sea been rougher, waves breaking against the icebergs would have made them more visible.[32] Because of a mix-up at Southampton, the lookouts had no binoculars; however, binoculars reportedly would not have been effective in the darkness, which was total except for starlight and the ship's own lights.[33] The lookouts were nonetheless well aware of the ice hazard, as Lightoller had ordered them and other crew members to "keep a sharp look-out for ice, particularly small ice and growlers".[d][34]

At 23:30, Fleet and Lee noticed a slight haze on the horizon ahead of them, but did not make anything of it. Some experts now believe that this haze was actually a mirage caused by cold waters meeting warm air – similar to a mirage in the desert – when Titanic entered Iceberg Alley. This would have resulted in a raised horizon, blinding the lookouts from spotting anything far away.[35][36]

Collision

Nine minutes later, at 23:39, Fleet spotted an iceberg in Titanic's path. He rang the lookout bell three times and telephoned the bridge to inform Sixth Officer James Moody. Fleet asked, "Is there anyone there?" Moody replied, "Yes, what do you see?" Fleet replied, "Iceberg, right ahead!"[37] After thanking Fleet, Moody relayed the message to Murdoch, who ordered Quartermaster Robert Hichens to change the ship's course.[38] Murdoch is generally believed to have given the order "hard a-starboard", which would result in the ship's tiller being moved all the way to starboard in an attempt to turn the ship to port.[33] This reversal of directions, when compared to modern practice, was common in British ships of the era. He also rang "full astern" on the ship's telegraphs.[24]

According to Fourth Officer Joseph Boxhall, Murdoch told Captain Smith that he was attempting to "hard-a-port around [the iceberg]", suggesting that he was attempting a "port around" manoeuvre – to first swing the bow around the obstacle, then swing the stern so that both ends of the ship would avoid a collision. There was a delay before either order went into effect; the steam-powered steering mechanism took up to 30 seconds to turn the ship's tiller,[24] and the complex task of setting the engines into reverse would also have taken some time to accomplish.[39] Because the centre turbine could not be reversed, both it and the centre propeller, positioned directly in front of the ship's rudder, were stopped. This reduced the rudder's effectiveness, therefore impairing the turning ability of the ship. Had Murdoch turned the ship while maintaining her forward speed, Titanic might have missed the iceberg with feet to spare.[40] There is evidence that Murdoch simply signalled the engine room to stop, not reverse. Lead Fireman Frederick Barrett testified that the stop light came on, but even that order was not executed before the collision.[41]

In the event, Titanic's heading changed just in time to avoid a head-on collision, but the change in direction caused the ship to strike the iceberg with a glancing blow. An underwater spur of ice scraped along the starboard side of the ship for about seven seconds; chunks of ice dislodged from upper parts of the berg fell onto her forward decks.[42] About five minutes after the collision, all of Titanic's engines were stopped, leaving the bow facing north and the ship slowly drifting south in the Labrador Current.[43]

Effects of the collision

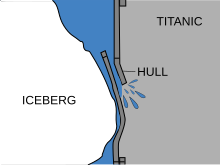

The impact with the iceberg was long thought to have produced a huge opening in Titanic's hull, "not less than 300 feet (91 m) in length, 10 feet (3 m) above the level of the keel", as one writer later put it.[44] At the British inquiry following the accident, Edward Wilding (chief naval architect for Harland & Wolff), calculating on the basis of the observed flooding of forward compartments forty minutes after the collision, testified that the area of the hull opened to the sea was "somewhere about 12 square feet (1.1 m2)".[45] He also stated that "I believe it must have been in places, not a continuous rip", but that the different openings must have extended along an area of around 300 feet, to account for the flooding in several compartments.[45] The findings of the inquiry state that the damage extended over a length of about 300 feet, and hence many subsequent writers followed this more vague statement. Modern ultrasound surveys of the wreck have found that the actual damage to the hull was very similar to Wilding's statement, consisting of six narrow openings covering a total area of only about 12 to 13 square feet (1.1 to 1.2 m2). According to Paul K. Matthias, who made the measurements, the damage consisted of a "series of deformations in the starboard side that start and stop along the hull ... about 10 feet (3 m) above the bottom of the ship".[46]

The gaps, the longest of which measures about 39 feet (12 m) long, appear to have followed the line of the hull plates. This suggests that the iron rivets along the plate seams snapped off or popped open to create narrow gaps through which water flooded. Wilding suggested this scenario at the British Wreck Commissioner's inquiry following the disaster, but his view was discounted.[46] Titanic's discoverer, Robert Ballard, has commented that the assumption that the ship had suffered a major breach was "a by-product of the mystique of the Titanic. No one could believe that the great ship was sunk by a little sliver."[47] Faults in the ship's hull may have been a contributing factor. Recovered pieces of Titanic's hull plates appear to have shattered on impact with the iceberg without bending.[48]

The plates in the central part of Titanic's hull (covering approximately 60 per cent of the total) were held together with triple rows of mild steel rivets, but the plates in the bow and stern were held together with double rows of wrought iron rivets which may have been near their stress limits even before the collision.[49][50] These "Best" or No. 3 iron rivets had a high level of slag inclusions, making them more brittle than the more usual "Best-Best" No. 4 iron rivets, and more prone to snapping when put under stress, particularly in extreme cold.[51][52] Tom McCluskie, a retired archivist of Harland & Wolff, pointed out that Olympic, Titanic's sister ship, was riveted with the same iron and served without incident for nearly 25 years, surviving several major collisions, including being rammed by a British cruiser.[53] When Olympic rammed and sank the U-boat U-103 with her bow, the stem was twisted and hull plates on the starboard side were buckled without impairing the hull's integrity.[53][54]

Above the waterline, there was little evidence of the collision. The stewards in the first class dining room noticed a shudder, which they thought might have been caused by the ship shedding a propeller blade. Many of the passengers felt a bump or shudder – "just as though we went over about a thousand marbles",[55] as one survivor put it – but did not know what had happened.[56] Those on the lowest decks, nearest the site of the collision, felt it much more directly. Engine Oiler Walter Hurst recalled being "awakened by a grinding crash along the starboard side. No one was very much alarmed but knew we had struck something."[57] Fireman George Kemish heard a "heavy thud and grinding tearing sound" from the starboard hull.[58]

The ship began to flood immediately, with water pouring in at an estimated rate of 7 long tons (7.1 t) per second, fifteen times faster than it could be pumped out.[59] Second engineer J. H. Hesketh and leading stoker Frederick Barrett were both struck by a jet of icy water in No. 6 boiler room and escaped just before the room's watertight door closed.[60] This was an extremely dangerous situation for the engineering staff; the boilers were still full of hot high-pressure steam and there was a substantial risk that they would explode if they came into contact with the cold seawater flooding the boiler rooms. The stokers and firemen were ordered to reduce the fires and vent the boilers, sending great quantities of steam up the funnel venting pipes. They were waist-deep in freezing water by the time they finished their work.[61]

Titanic's lower decks were divided into sixteen compartments. Each compartment was separated from its neighbour by a bulkhead running the width of the ship; there were fifteen bulkheads in all. Each bulkhead extended at least to the underside of E Deck, nominally one deck, or about 11 feet (3.4 m), above the waterline. The two nearest the bow and the six nearest the stern went one deck further up.[62]

Each bulkhead could be sealed by watertight doors. The engine rooms and boiler rooms on the tank top deck had vertically closing doors that could be controlled remotely from the bridge, lowered automatically by a float if water was present, or closed manually by the crew. These took about 30 seconds to close; warning bells and alternative escape routes were provided so that the crew would not be trapped by the doors. Above the tank top level, on the Orlop Deck, F Deck and E Deck, the doors closed horizontally and were manually operated. They could be closed at the door itself or from the deck above.[62]

Although the watertight bulkheads extended well above the water line, they were not sealed at the top. If too many compartments were flooded, the ship's bow would settle deeper in the water, and water would spill from one compartment to the next in sequence, rather like water spilling across the top of an ice cube tray. This is what happened to Titanic, which had suffered damage to the forepeak tank, the three forward holds, No. 6 boiler room, and a small section of No. 5 boiler room – a total of six compartments. Titanic was only designed to float with any two compartments flooded, but she could remain afloat with certain combinations of three or even four compartments – the first four – open to the ocean. With five or more compartments breached, however, the tops of the bulkheads would be submerged and the ship would continue to flood.[62][63]

Captain Smith felt the collision in his cabin and immediately came to the bridge. Informed of the situation, he summoned Thomas Andrews, Titanic's builder, who was among a party of engineers from Harland & Wolff observing the ship's first passenger voyage.[64] The ship was listing five degrees to starboard and was two degrees down by the head within a few minutes of the collision.[65] Smith and Andrews went below and found that the forward cargo holds, the mail room and the squash court were flooded, while No. 6 boiler room was already filled to a depth of 14 feet (4.3 m). Water was spilling over into No. 5 boiler room,[65] and crewmen there were battling to pump it out.[66]

Within 45 minutes of the collision, at least 13,500 long tons (13,700 t) of water had entered the ship. This was far too much for Titanic's ballast and bilge pumps to handle; the total pumping capacity of all the pumps combined was only 1,700 long tons (1,700 t) per hour.[67] Andrews informed the captain that the first five compartments were flooded, and therefore Titanic was doomed. Andrews accurately predicted that she could remain afloat for no longer than roughly two hours.[68]

From the time of the collision to the moment of her sinking, at least 35,000 long tons (36,000 t) of water flooded into Titanic, causing her displacement to nearly double from 48,300 long tons (49,100 t) to over 83,000 long tons (84,000 t).[69] The flooding did not proceed at a constant pace, nor was it distributed evenly throughout the ship, due to the configuration of the flooded compartments. Her initial list to starboard was caused by asymmetrical flooding of the starboard side as water poured down a passageway at the bottom of the ship.[70] When the passageway was fully flooded, the list corrected itself but the ship later began to list to port by up to ten degrees as that side also flooded asymmetrically.[71]

Titanic's down angle altered fairly rapidly from zero degrees to about four and a half degrees during the first hour after the collision, but the rate at which the ship went down slowed greatly for the second hour, worsening only to about five degrees.[72] This gave many of those aboard a false sense of hope that the ship might stay afloat long enough for them to be rescued. By 01:30, the sinking rate of the front section increased until Titanic reached a down angle of about ten degrees.[71] At about 02:15, Titanic's angle in the water began to increase rapidly as water poured into previously unflooded parts of the ship through deck hatches, disappearing from view at 02:20.[73]

15 April 1912

Preparing to abandon ship

At 00:05 on 15 April, Captain Smith ordered the ship's lifeboats uncovered and the passengers mustered. By now, many passengers were awaking, having noticed the engines and their accompanying vibrations had suddenly stopped.[63] He also ordered the radio operators to begin sending distress calls, which wrongly placed the ship on the west side of the ice belt and directed rescuers to a position that turned out to be inaccurate by about 13.5 nautical miles (15.5 mi; 25.0 km).[22][74] Below decks, water was pouring into the lowest levels of the ship. As the mail room flooded, the mail sorters made an ultimately futile attempt to save the 400,000 items of mail being carried aboard Titanic. Elsewhere, air could be heard being forced out by inrushing water.[75] Above them, stewards went door to door, rousing sleeping passengers and crew – Titanic did not have a public address system – and told them to go to the boat deck.[76]

The thoroughness of the muster was heavily dependent on the class of the passengers; the first-class stewards were in charge of only a few cabins, while those responsible for the second- and third-class passengers had to manage large numbers of people. The first-class stewards provided hands-on assistance, helping their charges to get dressed and bringing them out onto the deck. With far more people to deal with, the second- and third-class stewards mostly confined their efforts to throwing open doors and telling passengers to put on lifebelts and come up top. In third class, passengers were largely left to their own devices after being informed of the need to come on deck.[77] Many passengers and crew were reluctant to comply, either refusing to believe that there was a problem or preferring the warmth of the ship's interior to the bitterly cold night air. The passengers were not told that the ship was sinking, though a few noticed that she was listing.[76]

Around 00:15, the stewards began ordering the passengers to put on their lifebelts,[78] though again, many passengers took the order as a joke.[76] Some set about playing an impromptu game of association football with the ice chunks that were now strewn across the foredeck.[79] On the boat deck, as the crew began preparing the lifeboats, it was difficult to hear anything over the noise of high-pressure steam being vented from the boilers and escaping via the valves on the funnels above. Lawrence Beesley described the sound as "a harsh, deafening boom that made conversation difficult; if one imagines 20 locomotives blowing off steam in a low key it would give some idea of the unpleasant sound that met us as we climbed out on the top deck."[80] The noise was so loud that the crew had to use hand signals to communicate.[81]

Titanic had a total of 20 lifeboats, comprising 16 wooden boats on davits, eight on either side of the ship, and four collapsible boats with wooden bottoms and canvas sides.[76] The collapsibles were stored upside down with the sides folded in, and would have to be erected and moved to the davits for launching.[82] Two were stored under the wooden boats and the other two were lashed atop the officers' quarters.[83] The position of the latter would make them extremely difficult to launch, as they weighed several tons each and had to be manhandled down to the boat deck.[84] On average, the lifeboats could take up to 68 people each, and collectively they could accommodate 1,178 – barely half the number of people on board and a third of the number the ship was licensed to carry. The shortage of lifeboats was not because of a lack of space nor because of cost. Titanic had been designed to accommodate up to 68 lifeboats[85] – enough for everyone on board – and the price of an extra 32 lifeboats would only have been some US$16,000 (equivalent to $505,000 in 2023),[5] less than 1% of the $7.5 million that the company had spent on Titanic.

In an emergency at the time, lifeboats were intended to be used to transfer passengers off the distressed ship and onto a nearby vessel.[86][f] It was therefore commonplace for liners to have far fewer lifeboats than needed to accommodate all their passengers and crew, and of the 39 British liners of the time of over 10,000 long tons (10,000 t), 33 had too few lifeboat places to accommodate everyone on board.[88] The White Star Line desired the ship to have a wide promenade deck with uninterrupted views of the sea, which would have been obstructed by a continuous row of lifeboats.[89]

Captain Smith was an experienced seaman who had served for 40 years at sea, including 27 years in command. This was the first crisis of his career, and he would have known that even if all the boats were fully occupied, more than a thousand people would remain on the ship as she sank with little or no chance of survival.[63] Several sources later contended that upon grasping the enormity of what was about to happen, Captain Smith became paralysed by indecision, had a mental breakdown or nervous collapse, and was lost in a trance-like daze, being ineffective and inactive in attempting to mitigate the loss of life.[90][91] However, according to survivors, Smith took charge and behaved coolly and calmly during the crisis. After the collision, Smith immediately began an investigation into the nature and extent of the damage, personally making two inspection trips below deck to look for damage, and preparing the wireless men for the possibility of having to call for help. He erred on the side of caution by ordering his crew to begin preparing the lifeboats for loading, and to get the passengers into their lifebelts before he was told by Andrews that the ship was sinking. Smith was observed all around the decks, personally overseeing and helping to load the lifeboats, interacting with passengers, and trying to instil urgency to follow evacuation orders while avoiding panic.[92]

Fourth Officer Boxhall was told by Smith at around 00:25 that the ship would sink,[93] while Quartermaster George Rowe was so unaware of the emergency that after the evacuation had started, he phoned the bridge from his watch station to ask why he had just seen a lifeboat go past.[94] The crew was unprepared for the emergency, as lifeboat training had been minimal. Only one lifeboat drill had been conducted while the ship was docked at Southampton. It was a cursory effort, consisting of two boats being lowered, each manned by one officer and four men who merely rowed around the dock for a few minutes before returning to the ship. The boats were supposed to be stocked with emergency supplies, but Titanic's passengers later found that they had only been partially provisioned despite the efforts of the ship's chief baker, Charles Joughin, and his staff to do so.[95] No lifeboat or fire drills had been conducted since Titanic left Southampton.[95] A lifeboat drill had been scheduled for the Sunday morning before the ship sank, but was cancelled by Captain Smith for unknown reasons.[96]

Lists had been posted on the ship assigning crew members to specific lifeboat stations, but few appeared to have read them or to have known what they were supposed to do. Most of the crew were not seamen, and some even had no prior experience of rowing a boat. They were now faced with the complex task of coordinating the lowering of 20 boats carrying a possible total of 1,100 people a distance of 70 feet (21 m) down the sides of the ship.[84] Thomas E. Bonsall, a historian of the disaster, has commented that the evacuation was so badly organised that "even if they had the number [of] lifeboats they needed, it is impossible to see how they could have launched them" given the lack of time and poor leadership.[97] Indeed, not all of the lifeboats on board Titanic were launched before the ship sank.

By about 00:20, 40 minutes after the collision, the loading of the lifeboats was under way. Second Officer Lightoller recalled afterwards that he had to cup both hands over Smith's ears to communicate over the racket of escaping steam, and said, "I yelled at the top of my voice, 'Hadn't we better get the women and children into the boats, sir?' He heard me and nodded reply."[98] Smith then ordered Lightoller and Murdoch to "put the women and children in and lower away".[99] Lightoller took charge of the boats on the port side and Murdoch took charge of those on the starboard side. The two officers interpreted the "women and children" evacuation order differently; Murdoch took it to mean women and children first, while Lightoller took it to mean women and children only. Lightoller lowered lifeboats with empty seats if there were no women and children waiting to board, while Murdoch allowed a limited number of men to board if all the nearby women and children had embarked.[83]

Neither officer knew how many people could safely be carried in the boats as they were lowered and they both erred on the side of caution by not filling them. They could have been lowered quite safely with their full complement of 68 people, especially with the highly favourable weather and sea conditions.[83] Had this been done, an additional 500 people could have been saved; instead, hundreds of people, predominantly men, were left on board as lifeboats were launched with many seats vacant.[81][97]

Few passengers at first were willing to board the lifeboats and the officers in charge of the evacuation found it difficult to persuade them. Millionaire John Jacob Astor declared: "We are safer here than in that little boat."[100] Some passengers refused flatly to embark. J. Bruce Ismay, realising the urgency of the situation, roamed the starboard boat deck urging passengers and crew to board the boats. A trickle of women, couples and single men were persuaded to board starboard lifeboat No. 7, which became the first lifeboat to be lowered.[100]

Departure of the lifeboats

At 00:45, lifeboat No. 7 was rowed away from Titanic with an estimated 28 passengers on board, despite a capacity of 65. Lifeboat No. 6, on the port side, was the next to be lowered at 00:55. It also had 28 people on board, among them the "unsinkable" Margaret "Molly" Brown. Lightoller realised there was only one seaman on board (Quartermaster Robert Hichens) and called for volunteers. Major Arthur Godfrey Peuchen of the Royal Canadian Yacht Club stepped forward and climbed down a rope into the lifeboat; he was the only adult male passenger whom Lightoller allowed to board during the port side evacuation.[101] Peuchen's role highlighted a key problem during the evacuation: there were hardly any seamen to man the boats. Some had been sent below to open gangway doors to allow more passengers to be evacuated, but they never returned. They were presumably trapped and drowned by the rising water below decks.[102]

Meanwhile, other crewmen fought to maintain vital services as water continued to pour into the ship below decks. The engineers and firemen worked to vent steam from the boilers to prevent them from exploding on contact with the cold water. They re-opened watertight doors in order to set up extra portable pumps in the forward compartments in a futile bid to reduce the torrent, and kept the electrical generators running to maintain lights and power throughout the ship. Steward Frederick Dent Ray narrowly avoided being swept away when a wooden wall between his quarters and the third-class accommodation on E deck collapsed, leaving him waist-deep in water.[103] Two engineers, Herbert Harvey and Jonathan Shepherd (who had just broken his left leg after falling into a manhole minutes earlier), died in boiler room No. 5 when, at around 00:45, the bunker door separating it from the flooded No. 6 boiler room collapsed and they were swept away by "a wave of green foam" according to leading fireman Frederick Barrett, who barely escaped from the boiler room.[104]

In boiler room No. 4, at around 01:20 according to survivor trimmer George Cavell, water began flooding in from the metal floor plates below, possibly indicating that the bottom of the ship had also been holed by the iceberg. The flow of water soon overwhelmed the pumps and forced the firemen and trimmers to evacuate the boiler room.[105] Further aft, Chief Engineer Bell, his engineering colleagues, and a handful of volunteer firemen and greasers stayed behind in the unflooded Nos. 1, 2 and 3 boiler rooms and in the turbine and reciprocating engine rooms. They continued working on the boilers and the electrical generators in order to keep the ship's lights and pumps operable and to power the radio so that distress signals could be sent.[47] Several sources contend they remained at their posts until the very end, thus ensuring that Titanic's electrics functioned until the final minutes of the sinking, and died in the bowels of the ship. However, there is evidence to suggest when it became obvious that nothing more could be done, and the flooding in the forward compartments was too severe for the pumps to cope, some of the engineers and other crewmen abandoned their posts and came up onto Titanic's deck, but by this time all the lifeboats had left. Greaser Frederick Scott testified he saw eight of the ship's 35 engineers gathered at the aft end of the starboard boat deck.[106] None of the ship's 35 engineers and electricians survived.[107] Neither did any of the Titanic's five postal clerks, who were last seen struggling to save the mail bags they had rescued from the flooded mail room. They were caught by the rising water somewhere on D deck.[108]

Many of the third-class passengers were also confronted with the sight of water pouring into their quarters on E, F and G decks. Carl Jansson, one of the relatively small number of third-class survivors, later recalled:

Then I run down to my cabin to bring my other clothes, watch and bag but only had time to take the watch and coat when water with enormous force came into the cabin and I had to rush up to the deck again where I found my friends standing with lifebelts on and with terror painted on their faces. What should I do now, with no lifebelt and no shoes and no cap?[109]

The lifeboats were lowered every few minutes on each side, but most of the boats were greatly under-filled. No. 5 left with 41 aboard, No. 3 had 32 aboard, No. 8 left with 39[110] and No. 1 left with just 12 out of a capacity of 40.[110] The evacuation did not go smoothly and passengers suffered accidents and injuries as it progressed. One woman fell between lifeboat No. 10 and the side of the ship but someone caught her by the ankle and hauled her back onto the promenade deck, where she made a successful second attempt at boarding.[111] First-class passenger Annie Stengel had several ribs broken when a German-American doctor and his brother jumped into No. 5, squashing her and knocking her unconscious.[112][113] The lifeboats' descent was likewise risky. No. 6 was nearly flooded during the descent by water discharging out of the ship's side, but successfully made it away from the ship.[110][114] No. 3 came close to disaster when, for a time, one of the davits jammed, threatening to pitch the passengers out of the lifeboat and into the sea.[115]

By 01:20, the seriousness of the situation was now apparent to the passengers above decks, who began saying their goodbyes, with husbands escorting their wives and children to the lifeboats. Distress flares were fired every few minutes to attract the attention of any ships nearby and the radio operators repeatedly sent the distress signal CQD. Radio operator Harold Bride suggested to his colleague Jack Phillips that he should use the SOS signal, as it "may be your last chance to send it". Contrary to what Bride thought, SOS was not a new call, having been used many times before.[116] The two radio operators contacted other ships to ask for assistance. Several responded, of which RMS Carpathia was the closest, at 58 miles (93 km) away.[117] She was a much slower vessel than Titanic and, even driven at her maximum speed of 17 kn (20 mph; 31 km/h), would take four hours to reach the sinking ship.[118] Another to respond was SS Mount Temple, which set a course and headed for Titanic's position but was stopped en route by pack ice.[119]

Much nearer was SS Californian, which had warned Titanic of ice a few hours earlier. Apprehensive at his ship being caught in a large field of drift ice, Californian's captain, Stanley Lord, had decided at about 22:00 to halt for the night and wait for daylight to find a way through the ice field.[120] At 23:30, 10 minutes before Titanic hit the iceberg, Californian's sole radio operator, Cyril Evans, shut his set down for the night and went to bed.[121] On the bridge her third officer, Charles Groves, saw a large vessel to starboard around 10 to 12 mi (16 to 19 km) away. It made a sudden turn to port and stopped. If the radio operator of Californian had stayed at his post fifteen minutes longer, hundreds of lives might have been saved.[122] A little over an hour later, Second Officer Herbert Stone saw five white rockets exploding above the stopped ship. Unsure what the rockets meant, he called Captain Lord, who was resting in the chartroom, and reported the sighting.[123] Lord did not act on the report, but Stone was perturbed: "A ship is not going to fire rockets at sea for nothing," he told a colleague.[124]

![Image of a distress signal reading: "SOS SOS CQD CQD. MGY [Titanic]. We are sinking fast passengers being put into boats. MGY"](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/50/Titanic_signal.jpg/300px-Titanic_signal.jpg)

By this time, it was clear to those on Titanic that the ship was indeed sinking and there would not be enough lifeboat places for everyone. Some still clung to the hope that the worst would not happen: when Eloise Hughes Smith pleaded whether Lucian, her husband of two months, could go with her, Captain Smith ignored her, shouting again through his megaphone the message of women and children first. Lucian said, "Never mind, captain, about that; I will see that she gets in the boat", before telling Eloise, "I never expected to ask you to obey, but this is one time you must. It is only a matter of form to have women and children first. The ship is thoroughly equipped and everyone on her will be saved."[125] Tillie Taussig had to be dragged away from her husband (Emil Taussig) and put into lifeboat No. 8 with her daughter.[126] When Celiney Yasbeck saw Mr. Yasbeck would not be joining her in her boat, she tried in vain to return to him as it dropped to the sea.[126] Charlotte Collyer's husband Harvey called to his wife as two seamen hauled her into a lifeboat, "Go, Lottie! For God's sake, be brave and go! I'll get a seat in another boat!" Neither man survived.[125]

Other couples refused to be separated. Ida Straus, the wife of Macy's department store co-owner and former member of the United States House of Representatives Isidor Straus, told her husband: "We have been living together for many years. Where you go, I go."[125] They sat down in a pair of deck chairs and awaited their end.[127] The industrialist Benjamin Guggenheim changed out of his life vest and sweater into top hat and evening dress and declared his wish to go down like a gentleman.[47]

At this point, the vast majority of passengers who had boarded lifeboats were from first- and second-class. Few third-class (steerage) passengers had made it up onto the deck, and most were still lost in the maze of corridors or trapped behind gates and partitions that segregated the accommodation for the steerage passengers from the first- and second-class areas.[128] This segregation was not simply for social reasons, but was a requirement of United States immigration laws, which mandated that third-class passengers be segregated to control immigration and to prevent the spread of infectious diseases. First- and second-class passengers on transatlantic liners disembarked at the main piers on Manhattan Island, but steerage passengers had to go through health checks and processing at Ellis Island.[129] In at least some places, Titanic's crew appear to have actively hindered the steerage passengers' escape. Some of the gates were locked and guarded by crew members, apparently to prevent the steerage passengers from rushing the lifeboats.[128] Irish survivor Margaret Murphy wrote in May 1912:

Before all the steerage passengers had even a chance of their lives, the Titanic's sailors fastened the doors and companionways leading up from the third-class section ... A crowd of men was trying to get up to a higher deck and were fighting the sailors; all striking and scuffling and swearing. Women and some children were there praying and crying. Then the sailors fastened down the hatchways leading to the third-class section. They said they wanted to keep the air down there so the vessel could stay up longer. It meant all hope was gone for those still down there.[128]

A long and winding route had to be taken to reach topside; the steerage-class accommodation, located on C through G decks, was at the extreme ends of the decks, and so was the farthest away from the lifeboats. By contrast, the first-class accommodation was located on the upper decks and so was nearest. Proximity to the lifeboats thus became a key factor in determining who got into them. To add to the difficulty, many of the steerage passengers did not understand or speak English. It was perhaps no coincidence that English-speaking Irish immigrants were disproportionately represented among the steerage passengers who survived.[15] Many of those who did survive owed their lives to third-class steward John Edward Hart, who organised three trips into the ship's interior to escort groups of third-class passengers up to the boat deck. Others made their way through open gates or climbed emergency ladders.[130]

Some, perhaps overwhelmed by it all, made no attempt to escape and stayed in their cabins or congregated in prayer in the third-class dining room.[131] Leading Fireman Charles Hendrickson saw crowds of third-class passengers below decks with their trunks and possessions, as if waiting for someone to direct them.[132] Psychologist Wyn Craig Wade attributes this to "stoic passivity" produced by generations of being told what to do by social superiors.[108] August Wennerström, one of the male steerage passengers to survive, commented later that many of his companions had made no effort to save themselves. He wrote:

Hundreds were in a circle [in the third-class dining saloon] with a preacher in the middle, praying, crying, asking God and Mary to help them. They lay there and yelled, never lifting a hand to help themselves. They had lost their own will power and expected God to do all the work for them.[133]

Launching of the last lifeboats

By 01:30, Titanic's downward angle was increasing, but not more than 5 degrees, with an increasing list to port. The deteriorating situation was reflected in the tone of the messages sent from the ship: "We are putting the women off in the boats" at 01:25, "Engine room getting flooded" at 01:35, and at 01:45, "Engine room full up to boilers."[134] This was Titanic's last intelligible signal, sent as the ship's electrical system began to fail; subsequent messages were jumbled and unintelligible. The two radio operators nonetheless continued sending out distress messages almost to the very end.[135]

The remaining boats were filled much closer to capacity and in an increasing rush. No. 11 was filled with five people more than its rated capacity. As it was lowered, it was nearly flooded by water being pumped out of the ship. No. 13 narrowly avoided the same problem but those aboard were unable to release the ropes from which the boat had been lowered. It drifted astern, directly under No. 15 as it was being lowered. The ropes were cut in time and both boats got away safely.[136]

The first signs of panic were seen when a group of male passengers attempted to rush port-side lifeboat No. 14 as it was being lowered with 40 people aboard. Fifth Officer Lowe, who was in charge of the boat, fired three warning shots in the air to control the crowd without causing injuries.[137] No. 16 was lowered five minutes later. Among those aboard was stewardess Violet Jessop, who would also survive the sinking of one of Titanic's sister ships, Britannic, four years later, in the First World War.[138] Collapsible boat C was launched at 01:40 from a now largely deserted starboard area of the deck, as most of those on deck had moved to the stern of the ship. It was aboard this boat that White Star chairman and managing director J. Bruce Ismay, Titanic's most controversial survivor, made his escape from the ship, an act later condemned as cowardice.[134]

At 01:40, lifeboat No. 2 was lowered.[139] While it was still at deck level, Lightoller had found the boat occupied by men who, he wrote later, "weren't British, nor of the English-speaking race ... [but of] the broad category known to sailors as 'dagoes'."[140] After he evicted them by threatening them with his revolver (which was empty), he was unable to find enough women and children to fill the boat[140] and lowered it with only 25 people on board out of a possible capacity of 40.[139] John Jacob Astor saw his wife off to safety in No. 4 boat at 01:55 but was refused entry by Lightoller, even though 20 of the 60 seats aboard were unoccupied.[139]

The last boat to be launched was collapsible D, which left at 02:05 with 25 people aboard;[141] two more men jumped on the boat as it was being lowered.[142] The water had reached the boat deck and the forecastle was deep underwater. First-class passenger Edith Evans gave up her place in the boat, and ultimately died in the disaster. She was one of only four women in first class to perish in the sinking. Several survivors, including Third Class Passenger Eugene Daly and First Class passenger George Rheims, claimed to have seen an officer shoot one or two men during a rush for a lifeboat, then shoot himself. It was rumoured that Murdoch was the officer.[143]

Thomas Andrews was reportedly last seen in the first-class smoking room after approximately 02:05, apparently making no attempt to escape.[138][144] However, other reports suggest that Andrews may have been in the smoking room before 01:40, and that he then continued assisting with the evacuation;[145][146] he was reportedly seen throwing deck chairs into the ocean for passengers to cling to in the water,[145] and heading to the bridge, perhaps to search for Captain Smith.[146] Captain Smith carried out a final tour of the deck, telling the radio operators and other crew members: "Now it's every man for himself",[147] and told men attempting to launch collapsible boat A, "Well boys, do your best for the women and children, and look out for yourselves," and returned to the bridge just before the ship began its final plunge.[148] It is thought that he may have chosen to go down with his ship and died on the bridge when it submerged.[149][150] However, several survivors, including Harold Bride, saw Smith jump overboard from the bridge.[151] Mess steward Cecil Fitzpatrick claimed to have seen Andrews jump overboard with Smith.[145]

As most of the passengers and crew headed to the stern, where the priest Thomas Byles, a second-class passenger, was hearing confessions and giving absolutions, Titanic's band played outside the gymnasium.[152] Titanic had two separate bands of musicians. One was a quintet led by Wallace Hartley that played after dinner and at religious services while the other was a trio who played in the reception area and outside the café and restaurant. The two bands had separate music libraries and arrangements and had not played together before the sinking. Around 30 minutes after colliding with the iceberg, the two bands were probably called by Chief Purser McElroy or Captain Smith and ordered to play in the first class lounge.[153] Passengers present remember them playing lively tunes such as "Alexander's Ragtime Band". It is unknown if the two piano players were with the band at this time. The exact time is unknown, but the musicians later moved to the boat deck level of the First Class Entrance. Contrary to belief, there is no evidence they moved onto the deck itself,[154] but remained inside as steward Edward Brown claimed to have seen them at the top of the staircase in the first-class entrance.[155]

Part of the enduring folklore of the Titanic sinking is that the musicians played the hymn "Nearer, My God, to Thee" as the ship sank, though some regard this as dubious.[156] Nonetheless, the claim surfaced among the earliest reports of the sinking,[157] and the hymn became so closely associated with the Titanic disaster that its opening bars were carved on the grave monument of Titanic's bandmaster, Wallace Hartley.[158] Archibald Gracie emphatically denied it in his account, written soon after the sinking, and Harold Bride said that he had heard the band playing ragtime, then "Autumn",[159] by which he may have meant Archibald Joyce's then-popular waltz "Songe d'Automne" (Autumn Dream). George Orrell, the bandmaster of the rescue ship, Carpathia, who spoke with survivors, said: "The ship's band in any emergency is expected to play to calm the passengers. After Titanic struck the iceberg the band began to play bright music, dance music, comic songs – anything that would prevent the passengers from becoming panic-stricken ... various awe-stricken passengers began to think of the death that faced them and asked the bandmaster to play hymns. The one which appealed to all was 'Nearer My God to Thee'."[160]

According to Gracie, the tunes played by the band were "cheerful" but he did not recognise any of them, said that if they had played "Nearer, My God, to Thee" he "should have noticed it and regarded it as a tactless warning of immediate death to us all and one likely to create panic".[161] Several survivors who were among the last to leave the ship, including Brown, said the band continued playing until the ship began her final plunge.[153] Gracie said that the band stopped playing at least 30 minutes before the vessel sank. A. H. Barkworth, a first-class passenger, said: "I do not wish to detract from the bravery of anybody, but I might mention that when I first came on deck the band was playing a waltz. The next time I passed where the band was stationed, the members had thrown down their instruments and were not to be seen."[154] The band could have temporarily stopped playing to retrieve their lifebelts, then resumed.[8]

Bride heard the band playing as he left the radio cabin, which was by now awash, in the company of the other radio operator, Jack Phillips. He had fought a crewman who Bride thought was "a stoker, or someone from below decks", who had sneaked into the radio cabin and attempted to steal Phillips's lifebelt. Bride wrote later: "I did my duty. I hope I finished [the man]. I don't know. We left him on the cabin floor of the radio room, and he was not moving."[162] The two radio operators went in opposite directions, Phillips aft and Bride forward towards collapsible lifeboat B. Phillips perished.[162]

Gracie was also heading aft, but as he made his way towards the stern he found his path blocked by "a mass of humanity several lines deep, covering the boat deck, facing us"[163] – hundreds of steerage passengers, who had finally made it to the deck just as the last lifeboats departed. He gave up on the idea of going aft and jumped into the water to get away from the crowd.[163]

Last minutes of sinking

At about 02:15, Titanic's angle in the water began to increase rapidly as water poured into previously unflooded parts of the ship through deck hatches.[73] Her suddenly increasing angle caused what one survivor called a "giant wave" to wash along the ship from the forward end of the boat deck, engulfing many people.[164] The parties who were trying to launch collapsible boats A and B, including Sixth Officer Moody[165] and Gracie, were swept away along with the two boats (boat B floated away upside-down with Bride trapped underneath it, and boat A ended up partly flooded and with its canvas not raised). Bride and Gracie survived on boat B, but Moody perished.[166][167]

Lightoller, who had attempted to launch collapsible B, realised it would be futile to head aft, and dived overboard from the roof of the officers' quarters. He was sucked into the mouth of a ventilation shaft but was blown clear by "a terrific blast of hot air" and emerged next to the capsized lifeboat.[168] The forward funnel collapsed under its own weight, crushing several people to death struggling in the water, including first class passenger Charles Duane Williams,[169] as it fell into the water and only narrowly missing the lifeboat.[170] It closely missed Lightoller and created a wave that washed the boat 50 yards (46 m) clear of the sinking ship.[168] Those still on Titanic felt her structure shuddering as it underwent immense stresses. As first-class passenger Jack Thayer[171] described it:

Occasionally there had been a muffled thud or deadened explosion within the ship. Now, without warning she seemed to start forward, moving forward and into the water at an angle of about fifteen degrees. This movement with the water rushing up toward us was accompanied by a rumbling roar, mixed with more muffled explosions. It was like standing under a steel railway bridge while an express train passes overhead mingled with the noise of a pressed steel factory and wholesale breakage of china.[172]

Eyewitnesses saw Titanic's stern rising high into the air as the ship tilted down in the water. It was said to have reached an angle of 30–45 degrees,[173] "revolving apparently around a centre of gravity just astern of midships", as Lawrence Beesley later put it.[174] Many survivors described a great noise, which some attributed to the boilers exploding.[175] Beesley described it as "partly a groan, partly a rattle, and partly a smash, and it was not a sudden roar as an explosion would be: it went on successively for some seconds, possibly fifteen to twenty". He attributed it to "the engines and machinery coming loose from their bolts and bearings, and falling through the compartments, smashing everything in their way".[174]

After another minute, the ship's lights flickered once and then permanently went out, plunging Titanic into darkness. Jack Thayer recalled seeing "groups of the fifteen hundred people still aboard, clinging in clusters or bunches, like swarming bees; only to fall in masses, pairs or singly as the great afterpart of the ship, two hundred fifty feet of it, rose into the sky."[170]

Titanic's final moments

Titanic was subjected to extreme opposing forces – the flooded bow pulling her down while the air in the stern kept her to the surface – which were concentrated at one of the weakest points in the structure, the area of the engine room hatch. Shortly after the lights went out, the ship split apart. The submerged bow may have remained attached to the stern by the keel for a short time, pulling the stern to a high angle before separating and leaving the stern to float for a few moments longer. The forward part of the stern will have flooded very rapidly, causing it to tilt and then settle briefly until sinking.[176][177][178] The ship disappeared from view at 02:20, 2 hours and 40 minutes after striking the iceberg. Thayer reported that it rotated on the surface, "gradually [turning] her deck away from us, as though to hide from our sight the awful spectacle ... Then, with the deadened noise of the bursting of her last few gallant bulkheads, she slid quietly away from us into the sea."[179]

Titanic's surviving officers and some prominent survivors testified that the ship had sunk in one piece, a belief that was affirmed by the British and American inquiries into the disaster. Archibald Gracie, who was on the promenade deck with the band (by the second funnel), stated that "Titanic's decks were intact at the time she sank, and when I sank with her, there was over seven-sixteenths of the ship already underwater, and there was no indication then of any impending break of the deck or ship".[180] Ballard argued that many other survivors' accounts indicated that the ship had broken in two as she was sinking.[181] As the engines are now known to have stayed in place along with most of the boilers, the "great noise" heard by witnesses and the momentary settling of the stern were presumably caused by the break-up of the ship rather than the loosening of her fittings or boiler explosions.[182]

There are two main theories on how the ship broke in two – the "top-down" theory and the Mengot theory, so named for its creator, Roy Mengot.[183] The more popular top-down theory states that the breakup was centralized on the structural weak-point at the entrance to the first boiler room, and that the breakup formed first at the upper decks before shooting down to the keel. The breakup totally separated the ship down to the double bottom, which acted as a hinge connecting bow and stern. From this point, the bow was able to pull down the stern, until the double bottom failed and both segments of the ship finally separated.[183] The Mengot theory postulates that the ship broke from compression forces and not fracture tension, which resulted in a bottom-to-top break. In this model, the double-bottom failed first and was forced to buckle upwards into the lower decks, as the breakup shot up to the upper decks. The ship was held together by the B-Deck, which featured 6 large doubler plates – trapezoidal steel segments meant to prevent cracks from forming in the smokestack uptake while at sea – which acted as a buffer and pushed the fractures away. As the hull's contents spilled out of the ship, B-Deck failed and caused the aft tower and forward tower superstructures to detach from the stern as the bow was freed and sank.[183]

After they went under, the bow and stern took only about 5–6 minutes to sink 3,795 metres (12,451 ft), spilling a trail of heavy machinery, tons of coal and large quantities of debris from Titanic's interior. The two parts of the ship landed about 600 metres (2,000 ft) apart on a gently undulating area of the seabed.[184] The streamlined bow section continued to descend at about the angle it had taken on the surface, striking the seabed prow-first at a shallow angle[185] at an estimated speed of 25–30 mph (40–48 km/h). Its momentum caused it to dig a deep gouge into the seabed and buried the section up to 20 metres (66 ft) deep in sediment before it came to an abrupt halt. The sudden deceleration caused the bow's structure to buckle downwards by several degrees just forward of the bridge. The decks at the rear end of the bow section, which had already been weakened during the break-up, collapsed one atop another.[186]

The stern section seems to have descended almost vertically, probably rotating as it fell.[185] Empty tanks and cofferdams imploded as it descended, tearing open the structure and folding back the steel ribbing of the poop deck.[187] The section landed with such force that it buried itself about 15 metres (49 ft) deep at the rudder. The decks pancaked down on top of each other and the hull plating splayed out to the sides. Debris continued to rain down across the seabed for several hours after the sinking.[186]

Passengers and crew in the water

In the immediate aftermath of the sinking, hundreds of people were left struggling in the icy ocean, surrounded by debris from the ship. Titanic's disintegration during her descent to the seabed caused buoyant chunks of debris – timber beams, wooden doors, furniture, panelling and chunks of cork from the bulkheads – to rocket to the surface. These injured and possibly killed some of the swimmers; others used the debris to try to keep themselves afloat.[188]

With a temperature of −2 °C (28 °F), the water was lethally cold; Lightoller described the feeling of "a thousand knives" being driven into his body.[187] Sudden immersion into freezing water typically causes death within minutes, either from cardiac arrest, uncontrollable breathing of water, or cold shock (not, as commonly believed, from hypothermia);[189] almost all of those in the water died of cardiac arrest or other bodily reactions to freezing water within 15–30 minutes.[190] Only 13 of them were helped into the lifeboats, even though these had room for almost 500 more people.[191]

Those in the lifeboats were horrified to hear the sound of what Lawrence Beesley called "every possible emotion of human fear, despair, agony, fierce resentment and blind anger mingled – I am certain of those – with notes of infinite surprise, as though each one were saying, 'How is it possible that this awful thing is happening to me? That I should be caught in this death trap?'"[192] Jack Thayer compared it to the sound of "locusts on a summer night", while George Rheims, who jumped moments before Titanic sank, described it as "a dismal moaning sound which I won't ever forget; it came from those poor people who were floating around, calling for help. It was horrifying, mysterious, supernatural."[193]

The noise of the people in the water screaming, yelling, and crying was a tremendous shock to the occupants of the lifeboats, many of whom had up to that moment believed that everyone had escaped before the ship sank. As Beesley later wrote, the cries "came as a thunderbolt, unexpected, inconceivable, incredible. No one in any of the boats standing off a few hundred yards away can have escaped the paralysing shock of knowing that so short a distance away a tragedy, unbelievable in its magnitude, was being enacted, which we, helpless, could in no way avert or diminish."[192]

Only a few of those in the water survived. Among them were Gracie, Jack Thayer, and Lightoller, who made it to the capsized collapsible boat B. Around 12 crew members climbed on board collapsible B, and they rescued those they could until some 35 men were clinging precariously to the upturned hull. Realising the risk to the boat of being swamped by the mass of swimmers around them, they paddled slowly away, ignoring the pleas of dozens of swimmers to be allowed on board. In his account, Gracie wrote of the admiration he had for those in the water; "In no instance, I am happy to say, did I hear any word of rebuke from a swimmer because of a refusal to grant assistance... [one refusal] was met with the manly voice of a powerful man... 'All right boys, good luck and God bless you'."[194] Gracie said he heard men, including stoker Harry Senior and Entree cook Isaac Maynard, on collapsible B say that Captain Smith was in the water near the boat.[195] Fireman Walter Hurst said he thought the man who cried out, "All right boys. Good luck and God bless you", was Smith; Hurst said the man cheered the occupants on saying "Good boys! Good lads!" with "the voice of authority". Hurst, deeply moved by the swimmer's valor, reached out to him with an oar, but the man was dead.[196] Several other swimmers reached collapsible boat A, which was upright but partly flooded, as its sides had not been properly raised. Its occupants had to sit for hours in a foot of freezing water,[149] and many died of hypothermia during the night.

Farther out, the other eighteen lifeboats – most of which had empty seats – drifted as the occupants debated what, if anything, they should do to rescue the swimmers. Boat No. 4, having remained near the sinking ship, seems to have been closest to the site of the sinking at around 50 metres (160 ft) away; this had enabled two people to drop into the boat and another to be picked up from the water before the ship sank.[197] After the sinking, seven more men were pulled from the water, although two later died. Collapsible D rescued one male passenger who jumped in the water and swam over to the boat immediately after it had been lowered. In all the other boats, the occupants eventually decided against returning, probably out of fear that they would be capsized in the attempt. Some put their objections bluntly; Quartermaster Hichens, commanding lifeboat No. 6, told the women aboard his boat that there was no point returning as there were "only a lot of stiffs there".[198]

After about twenty minutes, the cries began to fade as the swimmers lapsed into unconsciousness and death.[199] Fifth Officer Lowe, in charge of lifeboat No. 14, "waited until the yells and shrieks had subsided for the people to thin out" before mounting an attempt to rescue those in the water.[200] He gathered together five of the lifeboats and transferred the occupants between them to free up space in No. 14. Lowe then took a crew of seven crewmen and one male passenger who volunteered to help, and then rowed back to the site of the sinking. The whole operation took about three-quarters of an hour. By the time No. 14 headed back to the site of the sinking, almost all of those in the water were dead and only a few voices could still be heard.[201]

Lucy, Lady Duff-Gordon, recalled after the disaster that "the very last cry was that of a man who had been calling loudly: 'My God! My God!' He cried monotonously, in a dull, hopeless way. For an entire hour, there had been an awful chorus of shrieks, gradually dying into a hopeless moan, until this last cry that I speak of. Then all was silent."[202] For some survivors, the dead silence that followed was worse even than the cries for help.[203] Lowe and his crew found four men still alive, one of whom died shortly afterwards. Otherwise, all they could see were "hundreds of bodies and lifebelts"; the dead "seemed as if they had perished with the cold as their limbs were all cramped up".[200]

In the other boats, there was nothing the survivors could do but await the arrival of rescue ships. The air was bitterly cold and several of the boats had taken on water. The survivors could not find any food or drinkable water in the boats, and most had no lights.[204] The situation was particularly bad aboard collapsible B, which was only kept afloat by a diminishing air pocket in the upturned hull. As dawn approached, the wind rose and the sea became increasingly choppy, forcing those on the collapsible boat to stand up to balance it. Some, exhausted by the ordeal, fell into the sea and drowned.[205] It became steadily more difficult for the rest to keep their balance on the hull, with waves washing across it.[206] Archibald Gracie later wrote of how he and the other survivors sitting on the upturned hull were struck by "the utter helplessness of our position".[207]

Rescue and departure

Titanic's survivors were rescued around 04:00 on 15 April by the RMS Carpathia, which had steamed through the night at high speed and at considerable risk, as the ship had to dodge numerous icebergs en route.[206] Carpathia's lights were first spotted around 03:30,[206] which greatly cheered the survivors, though it took several more hours for everyone to be brought aboard. The 30 or more men on collapsible B finally managed to board two other lifeboats, but one survivor died just before the transfer was made.[208] Collapsible A was also in trouble and was now nearly awash; many of those aboard (maybe more than half) had died overnight.[187] The remaining survivors were transferred from A into another lifeboat, leaving behind three bodies in the boat, which was left to drift away. It was recovered a month later by the White Star liner RMS Oceanic with the bodies still aboard.[208]

Those on Carpathia were startled by the scene that greeted them as the sun rose: "fields of ice on which, like points on the landscape, rested innumerable pyramids of ice."[209] Captain Arthur Rostron of Carpathia saw ice all around, including 20 large bergs measuring up to 200 feet (61 m) high and numerous smaller bergs, as well as ice floes and debris from Titanic.[209] It appeared to Carpathia's passengers that their ship was in the middle of a vast white plain of ice, studded with icebergs appearing like hills in the distance.[210]

As the lifeboats were brought alongside Carpathia, the survivors came aboard the ship by various means. Some were strong enough to climb up rope ladders; others were hoisted up in slings, and the children were hoisted in mail sacks.[211] The last lifeboat to reach the ship was Lightoller's boat No. 12, with 74 people aboard a boat designed to carry 65. They were all on Carpathia by 09:00.[212] There were some scenes of joy as families and friends were reunited, but in most cases hopes died as loved ones failed to reappear.[213]

At 09:15, two more ships arrived – Mount Temple and Californian, which had finally learned of the disaster when her radio operator returned to duty – but by then there were no more survivors to rescue. Carpathia had been bound for Fiume, Austria-Hungary (now Rijeka, Croatia), but as she had neither the stores nor the medical facilities to cater for the survivors, Rostron ordered that a course be calculated to return to New York, where the survivors could be properly looked after.[212] Carpathia departed the area, leaving the other ships to carry out a final, fruitless two-hour search.[214][215]

Aftermath

Grief and outrage

When Carpathia arrived at Pier 54 in New York on the evening of 18 April after a difficult voyage through pack ice, fog, thunderstorms and rough seas,[216][217] some 40,000 people were standing on the wharves, alerted to the disaster by newspaper stories relaying information gathered from radio telegraph messages sent by Carpathia and other ships. It was only after Carpathia docked – three days after Titanic's sinking – that the full scope of the disaster became public knowledge.[217]

Even before Carpathia arrived in New York, efforts were getting underway to retrieve the dead. Four ships chartered by the White Star Line succeeded in retrieving 328 bodies; 119 were buried at sea, while the remaining 209 were brought ashore to the Canadian port of Halifax, Nova Scotia,[216] where 150 of them were buried.[218] Memorials were raised in various places – New York, Washington, Southampton, Liverpool, Belfast and Lichfield, among others[219] – and ceremonies were held on both sides of the Atlantic to commemorate the dead and raise funds to aid the survivors.[220] The bodies of most of Titanic's victims were never recovered, and the only evidence of their deaths was found 73 years later among the debris on the seabed: pairs of shoes lying side by side, where bodies had once lain before eventually decomposing.[47]

The prevailing public reaction to the disaster was one of shock and outrage, directed against several issues and people: why were there so few lifeboats? Why had Ismay saved his own life when so many others died? Why did Titanic proceed into the ice field at full speed?[221] The outrage was driven not least by the survivors themselves; even while they were aboard Carpathia on their way to New York, Beesley and other survivors determined to "awaken public opinion to safeguard ocean travel in the future" and wrote a public letter to The Times urging changes to maritime safety laws.[222]

In places closely associated with Titanic, the sense of grief was deep. The heaviest losses were in Southampton, home port to 699 crew members and also home to many of the passengers.[223] Crowds of weeping women – wives, sisters, and mothers of crew members – gathered outside the White Star offices in Southampton for news of their loved ones.[224] Most of their missing loved ones were among the 549 Southampton residents who perished.[225] In Belfast, churches were packed, and shipyard workers wept in the streets. The ship had been a symbol of Belfast's industrial achievements, and there was a sense not only of grief but also of guilt, as those who built Titanic came to feel that they were responsible in some way for her loss.[226]

In Liverpool, the home base of the White Star Line, representatives of the company were confronted with such public anger that they were forced to announce the list of casualties from the balcony of the company headquarters.[227]

Public inquiries and legislation

In the aftermath of the sinking, public inquiries were set up in the United Kingdom and United States. The US inquiry began on 19 April under the chairmanship of Senator William Alden Smith,[228] and the British inquiry commenced in London under Lord Mersey on 2 May 1912.[229] They reached broadly similar conclusions: the regulations on the number of lifeboats that ships had to carry were out of date and inadequate;[230] Captain Smith had failed to take proper heed of ice warnings;[231] the lifeboats had not been properly filled or crewed; and the collision was the direct result of steaming into a danger area at too high a speed.[230] Both inquiries strongly criticised Captain Lord of Californian for failing to render assistance to Titanic.[232]

Neither inquiry found negligence by the parent company, International Mercantile Marine Co., or the White Star Line (which owned Titanic). The US inquiry concluded that those involved had followed standard practice and that the disaster could thus be categorised only as an "act of God".[233] The British inquiry concluded that Smith had followed long-standing practice, which had not previously been shown to be unsafe,[234] noting that British ships alone had carried 3.5 million passengers over the previous decade with the loss of just 73 lives,[235] and concluded that he had done "only that which other skilled men would have done in the same position". The British inquiry also warned that "what was a mistake in the case of the Titanic would without doubt be negligence in any similar case in the future".[234]